Blog topic suggested by CuMhara O’Holyhead

I remember as a new writer being afraid of using character archetypes. I mean not just stereotypes, but the wider, gentler tropes. The typical whatever. Hard Boiled Detective, Sexy Cat Burglar, Laconic Wise Man, Sassy Friend. I spent a lot of time coming up with very subtle characters and do you know what? I kept getting told in workshop that my characters were “muddy,” that they didn’t “stand out” or make an impression.

If everyone is a very subtle mix of unexpected qualities, well, they are all the same.

The first time I got a compliment on a character, I had given up on a deep, complex background and said, “Oh hell, I’ll just write Bridget Jones, but male.”

Seriously, it was like:

People already like archetypes. Look at the discourse around any popular fictional character. Fanfictions, artwork … they tend to lean into archetypes that the character comes close to, exaggerate them. We often complain of this in sequels, that a character becomes “a parody of themselves.” Part of this is because their archetype is what sticks most in the mind, and so the new writer will start with that.

Being an archetype doesn’t mean they aren’t a well-realized character.

Like many things in writing, character comes through in myriad decisions of craft and skill. A character is more than their backstory, after all. What are their actions? What happens around them? How do others react to them? Is there a gap between their self-perception and reality exposed by that?

The work of writing is the work of a thousand little decisions. Using an archetype frees you to work on other decisions. I already know this is a Disaffected Teen character, say, so I can work on the action, knowing that they will respond to it as a Disaffected Teen. I can play with our expectations of what a Disaffected Teen will do or care about, what a Disaffected Teen looks like, and this is where the character gains depth.

The grizzled detective snapped her fingers. “We need to put this on social media!”

Disaffected Teen brushed back his pink dreads. “Why are you all looking at me? Social media is an old person thing.”

We Inhabit Archetypes

The more I think about it, archetypes are something we apply to ourselves, in the real world. I’ve met my share of Soccer Dads and Not Like the Other Girls. I’m aware when I’m getting dressed that I’m going for Fun-Loving Flower Child or Beach Vacation Barbie.

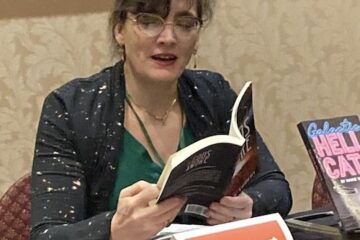

We stereotype ourselves. Most days, I’m what happens when Manic Pixie Dream Girl hits middle age:

Archetypes are aspirational. We want to be Cool Guy or Wine Aunt– maybe not all the time, but often enough that we’ll make choices that bend our personal presentation toward the archetypes we admire.

Archetypes are also assigned to people. Political ads are reminding me of that, as I see the same person portrayed as a working class hero and an out-of-touch elite, depending on who sponsored the ad. Some of how we portray ourselves, of how we perform personality, has to do with fear, with avoiding being labelled in a way we don’t want. I recently bought a pair of expensive shoes, and I thought, “But isn’t that too bougie for my sense of myself as a working-class gal?” I’m a computer programmer! That’s the whitest of collars.

I’m aware of containing both these archetypes: the girl who grew up poor and the professional woman who buys fancy shoes just because she wants them.

Maybe my own self-image has something to do with the way I populate my stories with Badass Babes or Thieves With Morals. How I quietly avoid Manic Pixies. Look at me, look at me… but please don’t see me.

Don’t Be Mean

If we’re all archetypes and they are so useful, why NOT use them? I think the main problem is that they might be used to make fun of people. They are the close cousins of stereotypes, after all. Ask yourself, am I playing into a stereotype? Will someone who sees themselves in this character be offended? Even portrayals you think of as positive can be hurtful. Have you ever had someone assume you were good at something because of how you looked? “But you’re a woman, you must be great at organizing parties!” Yeah, no.

I always try to imagine every character I write getting a chance to read the story. How do they feel about my portrayal? This question keeps me honest.

And maybe my hard-boiled detective goes home, changes into a cardigan, and becomes the crafty cat lady. Maybe the archetype she is seen as isn’t the one she wants to be seen as. There is character to explore in these contradictions. The more true we are, the more we violate our archetypes, the more inconsistent we become, the more muddy, the more, “So, a person?”

BUT… fiction is the art of using the untrue to uncover deeper truths. So we shave a little off a person, present them in one of their aspects, and do so honestly… as we would want to be seen when in our own hard-boiled phase. Strangely, this rings more true to the reader, because we don’t go through the world in all our muddiness and complexities. We shave ourselves, from situation to situation. I am my work-self. My work-self-when-with-buddies. My home-self. We contain multitudes, but we don’t see the whole multitude at once.

Honest fiction is best, anyway. That truth will ring for the readers, help them inhabit the story themselves, whatever their personal archetypes.