How did I go from a person who submits a lot of stories for publication to someone who gets acceptance letters? Did I just… get better? If so, how? And how can I pin the process down in a clear way to serve as advice for others?

When I look back at the stories I sent out to magazines ten or even five years ago, it’s hard not to cringe in embarrassment. “How did I ever think those were anything approaching good?”

Yet at the time I was sure they were good enough to publish. Not only were those stories bad, but I didn’t even understand they were bad. I didn’t understand them, period.

“Marie? How could you not understand a story you, yourself wrote?”

Thank you for asking, straw man. Let me break it down for you.

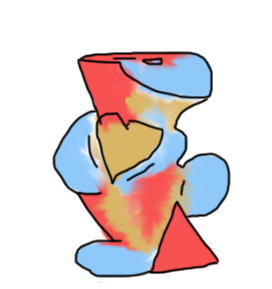

Remember when I wrote that long illustrated post about writing stories as Building An Invisible Vase? Cool analogy, right? Thing is, it’s true: the dang vase is invisible. Your conception of it can be different from the reality. So while I looked at my stories and saw them as comparable to the vases in stores, they really weren’t. (And yes, I could see that some of the vases in the store were crap vases, but that still didn’t mean my stories were better.)

| In my head | In reality |

|---|---|

|

|

“Oh no,” you cry, intended audience of aspirant writers, “then how do I know my stories are any good if I can’t trust my senses?”

Well, that’s part of it. The problem is: you can’t trust your senses and you have to trust your senses.

(I promise: this is not just some zen koan.)

Let’s get tangible. When I write a story, I do it by writing down words in an order that will make sense to a reader and convey ideas I want to convey.

That sounds stupidly basic. Stay with me.

Writing a story is no more or less than writing words down, so that’s what I do, and when I revise, I’m reading my words and thinking about how those words work on a sentence level, on a paragraph level, and then on a story level.

“No, really, were is the revelation here?”

Patience, Strawy. Newbie Marie, back in the day, didn’t trust herself enough. “Is this sentence conveying what I want it to? Hell if I know! I’ll write another sentence to be sure, and maybe use a pretty word in it.”

It’s not that I didn’t know how stories worked or how to write. I lacked the basic self-trust to edit.

Five, even ten years ago, I could do a few things well. I was great at witty dialog and the occassional description. A lifetime of TV had filled me with pithy asides, sarcasm and jokes.

Rather than writing a story and using these things to ornament that story, I wrote these elements I did well and tried to massage them into a story-shape. Kind of like starting with the surface, without a structure underneath. Imagine building a tree house out of pretty shingles and molding. Eventually you’d realize you need something underneath to hammer them to. An adult starts with the bare, simple structure boards. A kid hammers a structure board behind the assembled shingles just where needed and creates a rickety treehouse.

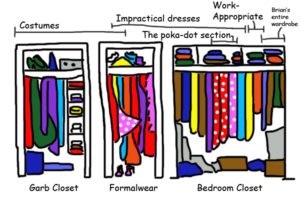

Not trusting your own craft can be comforting. It removes you a step from responsibility. It was like installing a bunch of third-party software instead of writing the simple script that does what you need done. We can all relate to that, right? Hrm… non programers – it was like pushing your belongings into boxes and closets rather than sorting it all so you can actually find what you need. It doesn’t take a special skill to sort things – it just takes a lot of decision-making, so we don’t do it.

It’s not just laziness – it’s also fear. Fear of failure. Fear of not being good enough, not having the good ideas or the good craft or anything interesting to say. The way to hide from that fear is to throw words out there and hope for accidental success.

Editing is decision-making. Lack of confidence lets us off the hook of that decision. “I don’t know what works. It will grow organically from the prose if I just keep throwing words down!” Yeah… like a “system” develops organically from clothes shoved into boxes. Maybe you do start having your casual clothes mostly in one box and formal clothes mostly in another, but the ad-hoc system will never be as strong as an actual, thoughtful sorting.

The revelation is nothing more than this: I am writing this story. I put words down in an order that makes sense. No one else. No magical muse or happenstance will make the story without you. It’s taking simple responsibility: trusting yourself. And it is looking critically at your decisions: Not trusting yourself.

The leap from being someone who submits stories for publication and someone who gets stories accepted happened when I trusted myself enough not to trust myself. When I started making cold, impersonal decisions about what works and what doesn’t. It started with me making some pretty arbitrary rules – always change one character’s gender after drafting. No more than three adjectives per paragraph. That sort of thing. I stopped trusting myself to just write well. I trusted myself to make these decisions to make my writing better.

Making an invisible vase, like making a real vase, is a technical process that requires skill and tools. Don’t be afraid to set the cutting knife to your vase.