I asked for blog post suggestions, willing to write about anything, and this topic was suggested by Tom Allman.

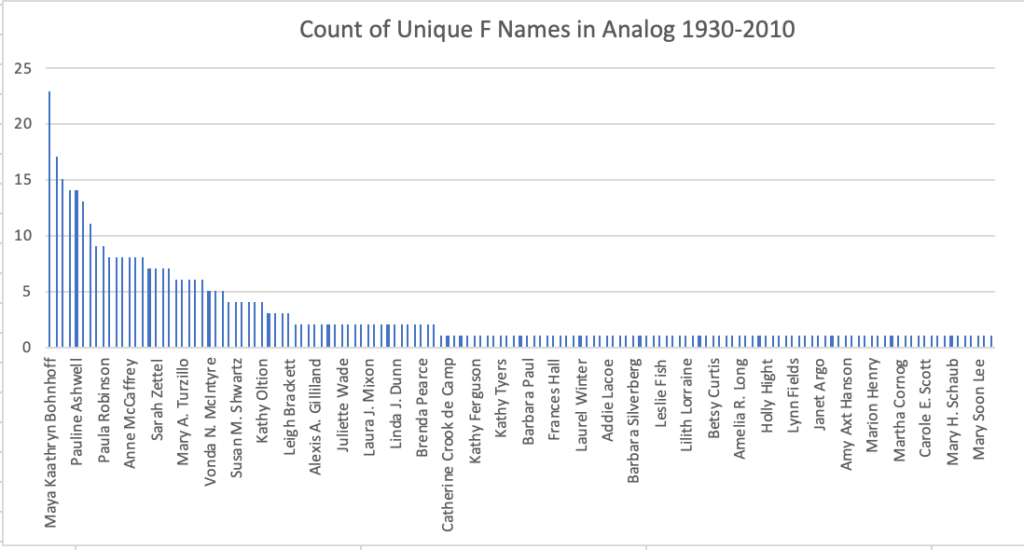

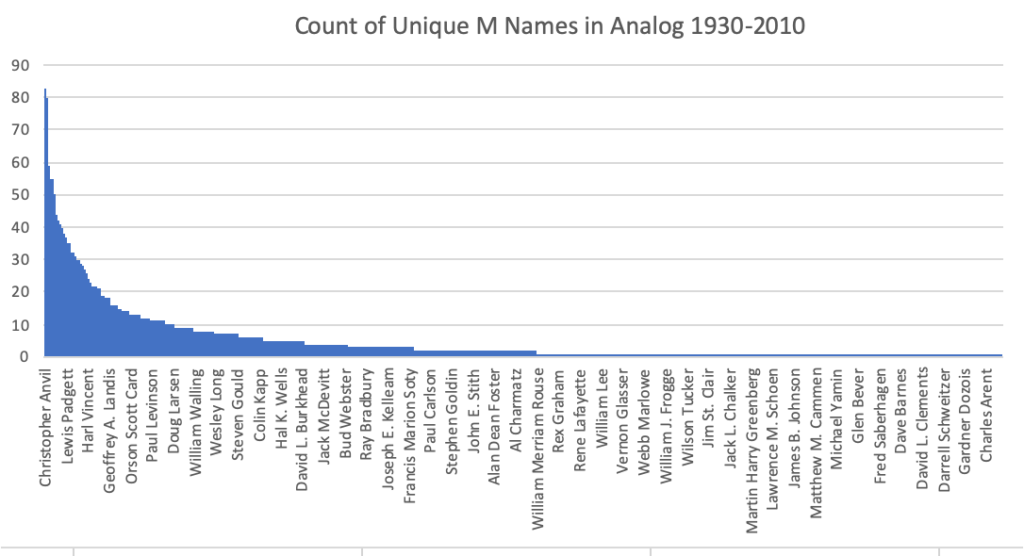

When I did my Visible Women in Science Fiction Magazines project, I identified 143 unique female names, across 410 credits. I actually found that the drop off from “stars” with over ten credits to the “one hits” was more gradual among female-seeming names than male-seeming names. There were more male names, and more male “stars” who had far more average credits than the female “stars”. More than half of male authors have at least two credits, less than half of female authors have at least two credits. I don’t know what I’m saying other than I feel like those one-hit wonders are important.

There were a lot of one-hit wonder women in pulp. I’m not going to embarrass myself by pretending to know more about Women in Pulp than I do, rather I will focus on three women I know something about from my own pleasure reading and research.

Clare Winger Harris –

Clare Winger Harris might be the first woman to publish science fiction under her own name, and a professor at my university put together a collection of her work, which I read and enjoyed immensely. (The Artificial Man and Other Stories – Brad Ricca)

I had already read some of her stuff in my science fiction magazines project and so that made me feel “in the know” when I was invited to join him at a launch event at Appletree Books.

Ms. Harris wrote a historical fantasy novel that was published in 1923, and then in 1927 she sold a story to Amazing Stories through a contest, and ooooh look at the backhanded compliment from Hugo Gernsbeck himself in announcing the winners:

That the third prize winner should prove to be a woman was one of the surprises of the contest, for, as a rule, women do not make good scientification writers, because their education and general tendencies on scientific matters are usually limited. But the exception, as usual, proves the rule, the exception in this case being extraordinarily impressive.

quoted in Brad Ricca’s introduction to “Artificial Man and Other Stories”

Hugo, you twat.

Her stories are fascinating, and bring in so many concepts that would later become their own sub-genres. Intelligent planets. World-spanning cities. Animals raised to intelligence.

And she was living in Lakewood, Ohio, when she sold her first stories, too! So yeah, I claim her as a Cleveland Science Fiction Founder.

Doris Pitkin Buck –

I agreed to write an introduction essay for Journey Press’s Rediscovery, an anthology series reprinting short stories by women from the golden age of science fiction. I was assigned Doris Pitkin Buck, and found her a treat.

Doris Pitkin Buck told Anthony Boucher of F&SF in 1954 that she was just a housewife, “I take in writing as some women take in wash.” Quite the claim for a prolific freelance author churning out nonfiction titles and regular appearances in The New Yorker, aside from radio scripts and trade papers. Not to mention her day job as a museum publicist and working public relations for the Department of the Interior! She seems about as housewifely as James Bond.

Perhaps she was being modest, or deflecting backlash before it even began. Or it was yet another excellent bon mot from a sharp mind always on the lookout for social commentary. You can certainly feel her snark in her work, which always seems to have a wink at the reader behind the characters’ backs. If I had a time machine, I would definitely make one of my first stops cocktails in Manhattan with Doris.

Andre Norton –

This giant of the industry grew up in Collinwood and worked for thirty years for Cleveland Public Libraries. Why don’t we have a statue of her downtown? Maybe holding a cat? She wrote mostly novels, not short stories, and her first was published in 1938, though she apparently wrote it while still a student at Collinwood High, before 1930. (I feel you, Andre!)

She attended my alma mater, or at least part of it, Western Reserve University, and majored in English.

Her work was part of the birth of many sub-genres: the lost colony, the portal fantasy, the sword-and-sorceress. I recently read and re-read as many of her books as I could get my hands on for a class I taught on her. You can really feel her passion for anthropology, archeology, and cute furry animals. Endings were her weak spot, and that might be why she also created the Never Ending Novel Series genre.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned through my reading and fascination with my foremothers in pulpy fiction, it is that they are very different from one another. Here we have a suburban housewife, a Manhattan socialite, and a cat-loving librarian, all inventing new worlds of thought alongside the men of their time. I just wish I knew more about the women who only sold one story once in 1954. I imagine their stories are as varied and compelling.